‘There’s

a man,’ Alice said. ‘She’s with a man.’ She scrubbed the bus window with a

bunched-up brown glove. May sat down heavily beside her, still probing a blasted

peppermint. She leaned forward, her menthol breath ruining all Alice’s work on

the window.

The duo are outraged because this is a tour for Retired Ladies,

and not only is Mrs Nash not actually retired (although she is of an age for it),

but she has brought her son with her. As you can imagine, he is an object of

great curiosity to the ladies – but he turns out to be very odd indeed.

Clare

Boylan’s Some Retired Ladies on a Tour follows the disparate group as

they make their way to various shabby, run-down, seaside hotels and boarding

houses. At one place they are served up cold prunes and custard. And when the

same unappetising mess appears as pudding a couple of days later at another

location, the ladies joke that it’s been sent on.

From the outset nothing is quite as it should be.

The

drive was a disappointment. They had expected the driver to be a comedian who

would take them all on, call them darling, sing over the microphone so they

could join in and jolly up the shy ones. Instead there was a snivelling young

pup who got his thrills speeding around corners and wouldn’t stop to let them

go to the toilet. By the time they got to the first resort the outgoing ones

were bored and bad tempered. The oldest ladies were purple and rigid with

misery.

And when they arrive at their first hotel things aren’t much

better, because the driver disappears into a pub, leaving them ‘teetering’ and

shivering on the edge of a cliff to make their own way to the hotel. However,

at reception they are cheered by a ‘bit of commotion’ that makes them forget

the dismal journey, for Mrs Nash, as the receptionist tells the manager, wants

to sleep with her son…

Joe is a handsome man, aged about 45, with light curly hair,

and a boyish diffident smile. But there is something about him that is not

quite right. He is almost like a child, and seems ‘a transparent creature, a

daddy-long-legs’. He rarely speaks, but does sing at their evening concerts (these

Retired Ladies are nothing if not resourceful – they carry their own luggage,

as well as providing their own entertainment).

Mrs Nash, with her shrivelled face and her green Crimplene

turban, tells Alice that on his way to work one day Joe fell down with a clot

and was brought home in a bread van.

…Joe

was the only thing that had ever actually belonged to her. She wasn’t about to

let him go to a clot. The clot wouldn’t dare strike while she was around.

Mrs Nash doesn’t have many friends, on account of Joe, which

is understandable I think. She keeps tight hold of her him, watching his every

move, supervising everything he does. They share a room, and even go to the toilet hand in hand

for, she says, Joe is ill, and must be cared for. I won’t tell you what

happens, but Joe really is ill, but not in the way she says, and he really does

need proper care. For Joe has a Past, and his past is not pleasant, and poor Mrs

Nash hides his terrible secret and protects him from the world (and the world from him). However, he appears harmless enough, and Retired

Lady Doris Moore becomes more than a little obsessed by him. Force to give up

work through ill health, she was once manageress at Imperial Meats.

By

the time she was thirty, Doris realised she hadn’t bothered to look for a man.

She had been too busy looking for jumpers. Her big achievement was learning to

knit. She came to look on the cold as a constant; warmth and sunshine were interruptions.

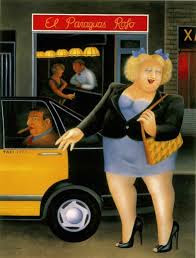

She’s a large lady, who favours brightly coloured knitted garments,

likes a drink and a laugh, and loves to be centre of attraction. At the end of

the holiday, convinced that Joe admires her, she takes matters into her own

hands and, to her horror, discovers Joe’s guilty secret. Things could get very

nasty indeed, but there’s a farcical element to the whole incident, and all

ends well.

Mrs Nash and her son depart in a taxi for Birkenhead (where

she keeps a market stall) and Doris, whose behaviour is the talk of the tour, brazens

it out, joining the other Retired Ladies for the journey home. In fact the last

night proves to be the high spot of the holiday, bringing a touch of spice into

the Retired Ladies’ dull lives.

For the Ladies (who seem to belong to some kind of club) are

all lonely, all on their own, except Mrs Nash, of course – and she must be as

lonesome as the others, for her need to keep a constant watch on her son

prevents any other social interaction. And the others seem to be as friendless

as she. The group reminded me a bit of Elizabeth Taylor’s Mrs Palfrey at the

Claremont where the elderly men and women who have come down in the world are reduced

to living in a hotel (which has also come down in the world). Despite the humour

of Boylan’s tale, there’s the same sense of sadness and loneliness, displacement

and isolation. Their holiday gives them a few days of companionship, in a

different environment.

I’ve never read any Clare Boylan before, but I enjoyed this

tale (another in The Penguin Book of Modern Women’s Short Stories). She set the

scene well, and I could picture the out of season seaside resorts, as unloved

and lonely as the Retired Ladies.

.jpg)